Test Header

Having commandeered an enchanted vessel, Don Quixote tries to put the exasperated Sancho at ease as they putter down the River Elba:

What dost thou want, unsatisfied in the very heart of abundance? Art thou, perchance, tramping barefoot over the Riphaean mountains, instead of being seated on a bench like an archduke on the tranquil stream of this pleasant river, from which in a short space we shall come out upon the broad sea? But we must have already emerged and gone seven or eight hundred leagues; and if I had here an astrolabe to take the altitude of the pole, I could tell thee how many we have traveled, though either I know little, or we have already crossed or shall shortly cross the equinoctial line which parts the two opposite poles midway.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Don Quixote [1605, 1615], trans. John Ormsby (Gutenberg, 1997, eBook #996). Spanish edition (Gutenberg, 1999, eBook #2000). He does, in fact, know little—they are still well within view of their port of origin, and his understanding of nautical navigation throughout the chapter is quite ill-informed, but he knows enough to lament the absence of the astrolabe. The world that Don Quixote inhabits is one of overlapping realities and fictions; though reimagined by his overzealous chivalry and an unwavering confidence in the fantastic, his actions play out in—and provoke response from—a realistic material world.And, as an early example of metafiction, the concept of reality is further muddled by Cervantes’s insistence that the tale is true, and that history itself is being altered by the action of his fictional characters.

The misalignment between expectation and reality in navigation, captured comically by Cerevantes, is not limited to fiction on the Iberian peninsula. Don Quixote’s missing marine astrolabe was an instrument designed for the moment sailors crossed out of sight from shore, a new method of navigation no longer reliant upon the visual cues of a predictable coast for guidance. And yet, forces shaping the object’s production and regulation remained necessarily land-bound to the port cities of Lisbon and Seville. This restriction aligned the object’s design with the emergence of scholastic and theoretical work by state cosmographers. Its use, however, submitted the tool to the harsh physical reality of nautical operation. Over the long sixteenth century, these two worlds of knowledge shaping the object were often in conflict, but always entangled. This paper will follow the path of the astrolabe making its way to sea, from metal workshop to final inspection, in Spain and Portugal. Each stage was a potential point of contention, the power of beached pilots diminished but unyielding against the labyrinthine bureaucracy concocted by cosmographers. These two recurring characters push and pull at the nautical astrolabe: the cosmographer assigned to describe the world with his charts, maps, and formulae, and the pilot to trace the world with his own movement across oceans wide.

The complexities of both Iberian “seaborne empires” have already been broadly contextualized by authors like C.R. Boxer (1991) and Pablo E. Pérez-Mallaína (1998). Recent scholarship has started to unpack institutional systems of knowledge-sharing and control, research by Alison Sandman (2008) and Antonio Sánchez (2016) grounded in documents from state archives. Building on this line of inquiry, the essay that follows intends to look at how remaining physical evidence reflects—or fails to reflect—contemporary written descriptions: of astrolabe designs specified in navigational treatises, of perceived aesthetics of astrolabes in shipwreck narratives, of bureaucratic management of astrolabes in official documents of state. The number of known surviving instruments has increased significantly since the formative works of Alan Stimson (1985) and David Waters (1966), with over one hundred objects now indexed by Filipe Castro and his team (2020). By taking a cross-section through this catalogue of extant objects, we might better understand how choices of material, form, and marking were impacted by both practical and theoretical constraints, by different ways of knowing and interacting with the material world.

Origin Stories

Implementation of the nautical astrolabe is generally credited to one or another of King Joao II’s advisors in late fifteenth century Portugal, though its form evolved from a much older instrument.One of the earliest historical accounts is that of Manuel Telles da Silva, Marquês de Alegrete, in 1689, who tells of a council set up by the king including a military hero, the king’s own two personal physicians, and “Martino Bohemo, ea aetate peritissimis Mathematics,” to work together to devise a way for Portuguese pilots to navigate “licet in vasto novoque pelago” [although in a vast and new sea]; the group, “post indefessum studium, longamque meditationem” [after tireless study and prolonged meditation], arrive at a modified planispheric astrolabe. Author’s translation. Manuel Telles da Silva, Marquês de Alegrete, De rebus gestis Joanni II (Ulyssipone [Lisbon]: Michael Manescal, 1689), 151–153. David Waters and other scholars have already posited the likely evolution from planispheric to nautical astrolabe, and identified various physical comparisons between the two instrument variants. See for example, David Waters, The Sea- or Mariner’s Astrolabe (Coimbra, Portugal: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1966), 6. The planispheric astrolabe was a tool of astronomers, perfected in the medieval Islamic world as a precision map of the sky and used only rarely for calculations relating to way-finding. Most critical for the nautical astrolabe’s development, the back face of the planispheric astrolabe featured a scale for measuring altitude, sighted through a rotating alidade.For a brief overview of the use of the planispheric astrolabe in the early Islamic world—including the explicit mention in the Qur’an of using the cosmos to navigate—see Emilie Savage-Smith, “2. Celestial Mapping,” in The History of Cartography, Volume 2, Book 1: Cartography in the Traditional Islamic and South Asian Societies, ed. J. B. Harley and David Woodward (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1992). These features, eventually optimized for marine conditions, allowed pilots to observe the altitude of the sun; after adjusting this measured angle with the day’s solar declination, the resultant difference would equal the ship’s latitude and thus identify their location north to south on open water.

New instruments were tested on voyages like Vasco da Gama’s first India run, his ships equipped with two early variants of the same tool: bulky wooden astrolabes “três palmos de diâmetro,” or roughly 26 inches wide, were accompanied by delicate brass “chapa” [plate] astrolabes.João de Barros, [Décadas] Da Asia (1539), quoted in David Waters, The Sea- or Mariner’s Astrolabe (Coimbra, Portugal: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1966), 9. During a stop along the east coast of Africa, da Gama was introduced to a local pilot who recognized the methods with which the instruments were deployed: “This pilot showed no surprise on seeing the large wooden and metal astrolabes belonging to the Portuguese, as [local people] had long used brass triangular instruments and quadrants for astronomical observations […] though they did not use these instruments in navigation.”Commentary by historian and editor [James Stanier] Clarke, after Portuguese historians Manuel de Faria e Sousa and Jerónimo Osório da Fonseca of the sixteenth century. Robert Kerr ed., “Chapter VI. History of the discovery and conquest of India by the Portuguese, between the years 1497 and 1525: from the original Portuguese of Herman Lopes de Castaneda,” in A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels, Volume II (Edinburgh, Scotland: William Blackwood, 1824). Although late fifteenth century Portuguese navigators were among the first to employ these tools in this way, the technique of finding position by referencing the cosmos, like the nautical astrolabe’s form, was the development of much older knowledge from the East.

This state of liminality is suitable, perhaps, for an object devised to “navigate by shadows,”Francisco Rodrigues, “Chapter To Explain How You Should Navigate By Shadows,” 304. untethered from known shores and sailing off into a rapidly expanding global world.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Laoreet sit amet cursus sit amet dictum sit amet justo. Ultricies mi eget mauris pharetra et ultrices neque ornare aenean. Vestibulum mattis ullamcorper velit sed ullamcorper morbi tincidunt ornare. Venenatis cras sed felis eget velit aliquet sagittis id consectetur. Sed nisi lacus sed viverra tellus in hac habitasse platea. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Sit amet tellus cras adipiscing enim eu turpis egestas. Dictum varius duis at consectetur lorem donec massa sapien faucibus.

Dictum varius duis at consectetur lorem donec massa sapien faucibus. Porta nibh venenatis cras sed felis eget velit aliquet sagittis. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. In mollis nunc sed id semper risus in hendrerit gravida. Sit amet tellus cras adipiscing enim eu turpis egestas. Egestas purus viverra accumsan in nisl nisi scelerisque eu. Sed risus ultricies tristique nulla aliquet enim tortor at auctor.

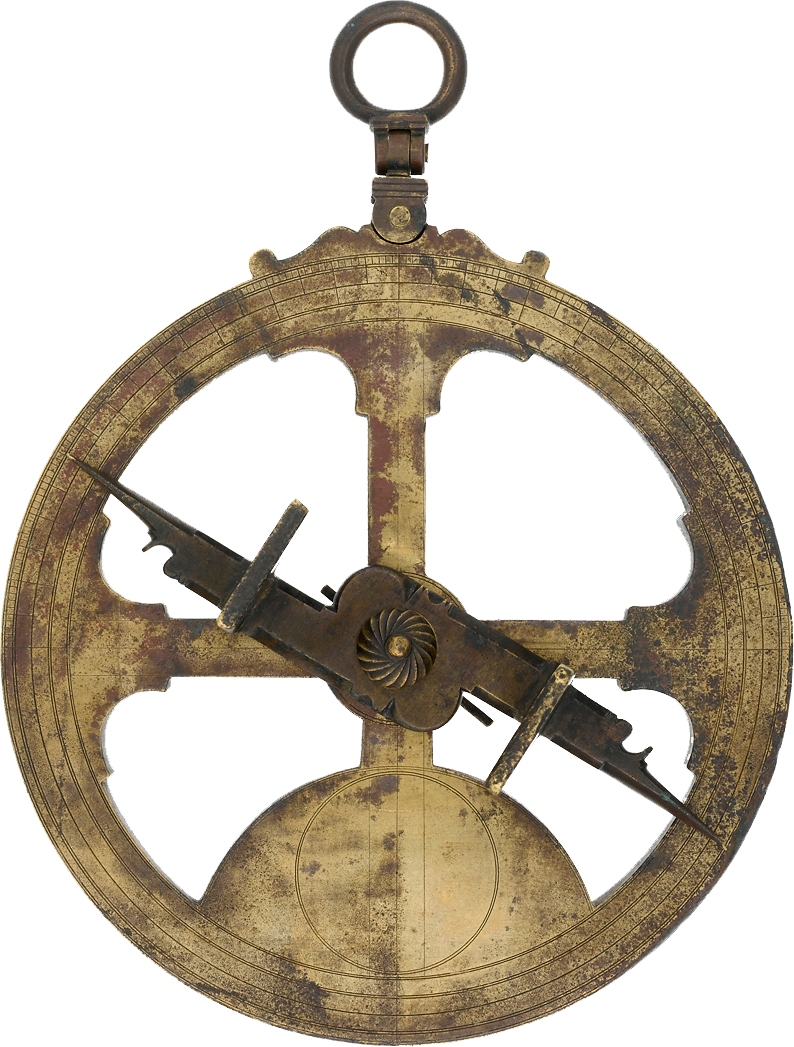

Greenwich / Valencia Astrolabe, CMAC No. 4: Frontal view, (c) National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK

Sit amet tellus cras adipiscing enim eu turpis egestas. Venenatis cras sed felis eget velit aliquet sagittis id consectetur.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Laoreet sit amet cursus sit amet dictum sit amet justo. Ultricies mi eget mauris pharetra et ultrices neque ornare aenean. Vestibulum mattis ullamcorper velit sed ullamcorper morbi tincidunt ornare. Venenatis cras sed felis eget velit aliquet sagittis id consectetur. Sed nisi lacus sed viverra tellus in hac habitasse platea. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Sit amet tellus cras adipiscing enim eu turpis egestas. Dictum varius duis at consectetur lorem donec massa sapien faucibus.